Pathways to Decriminalization of Homosexual Acts

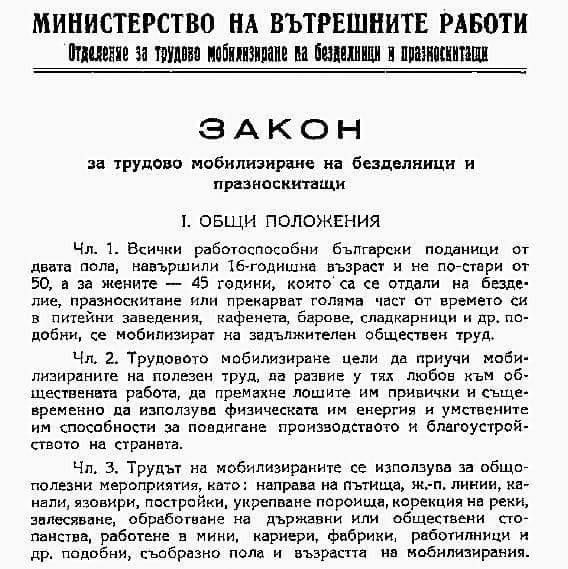

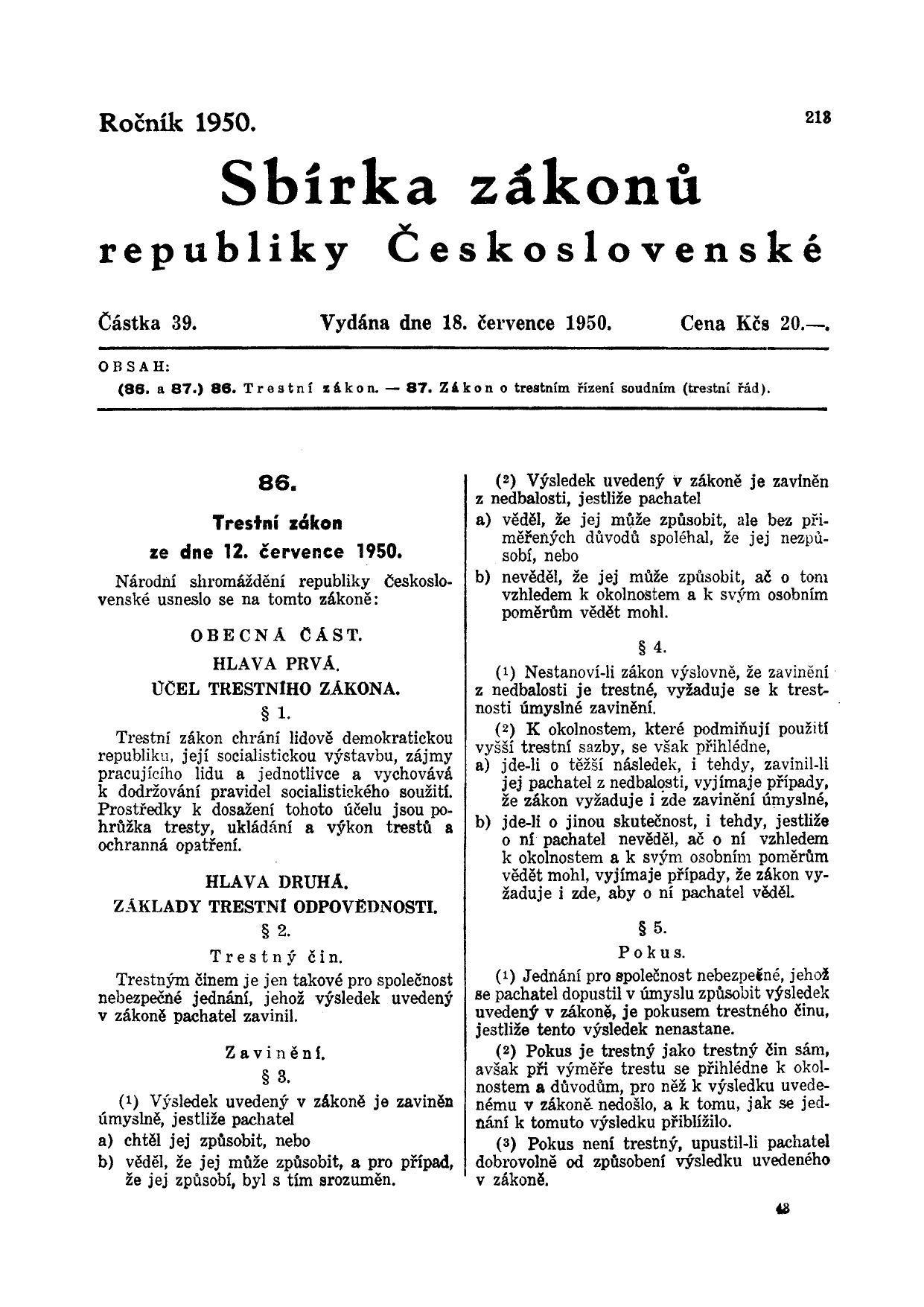

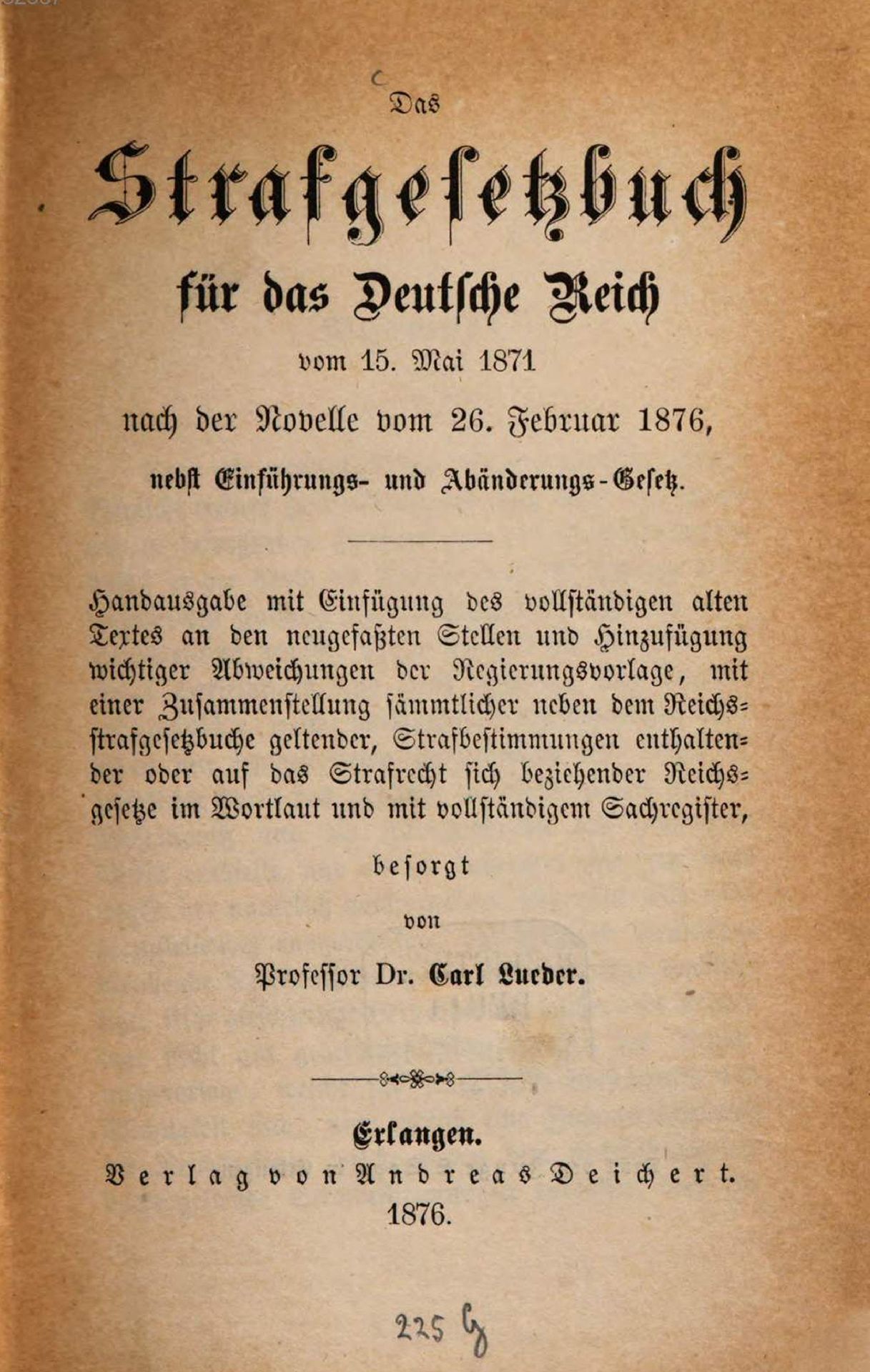

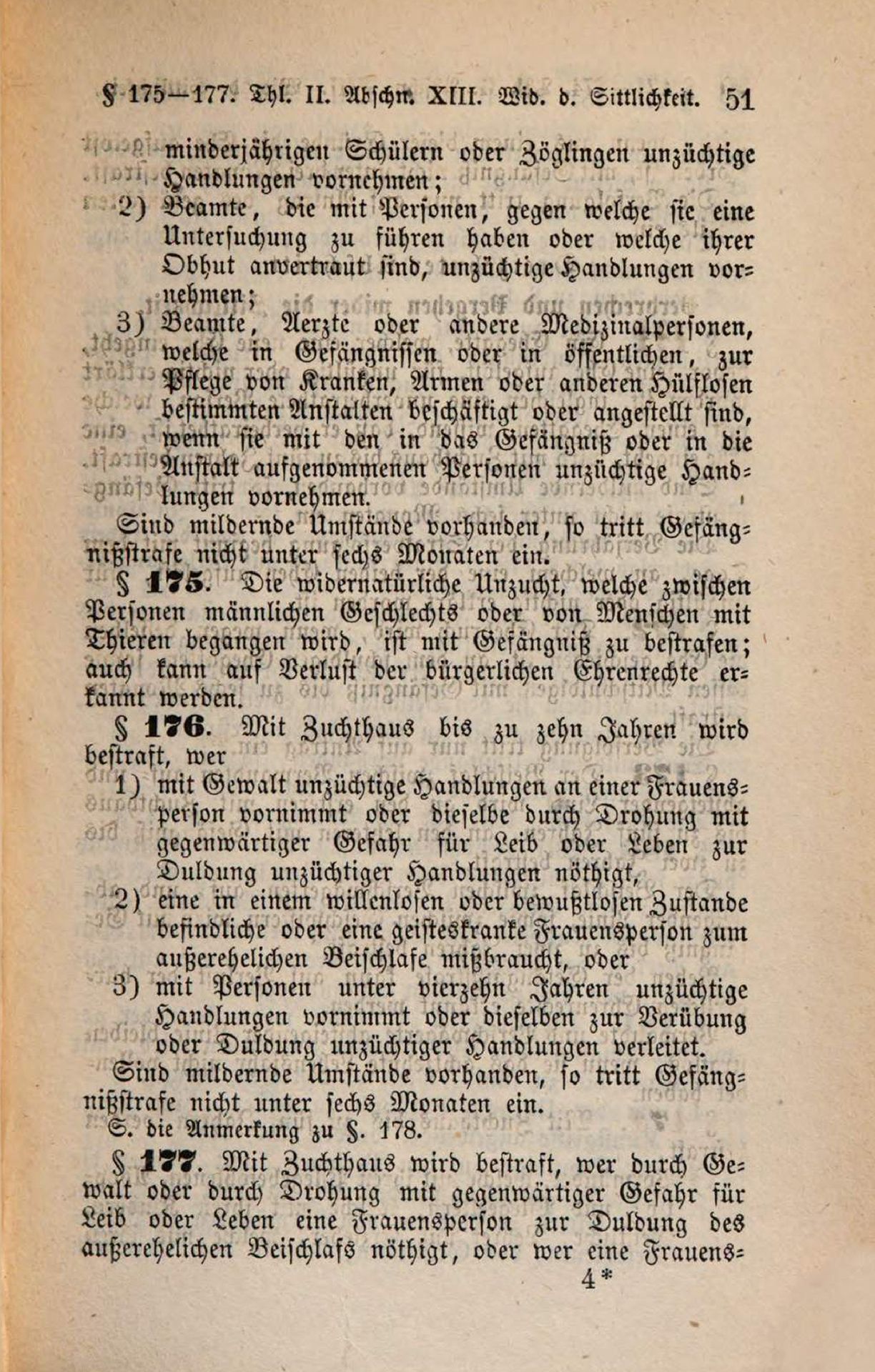

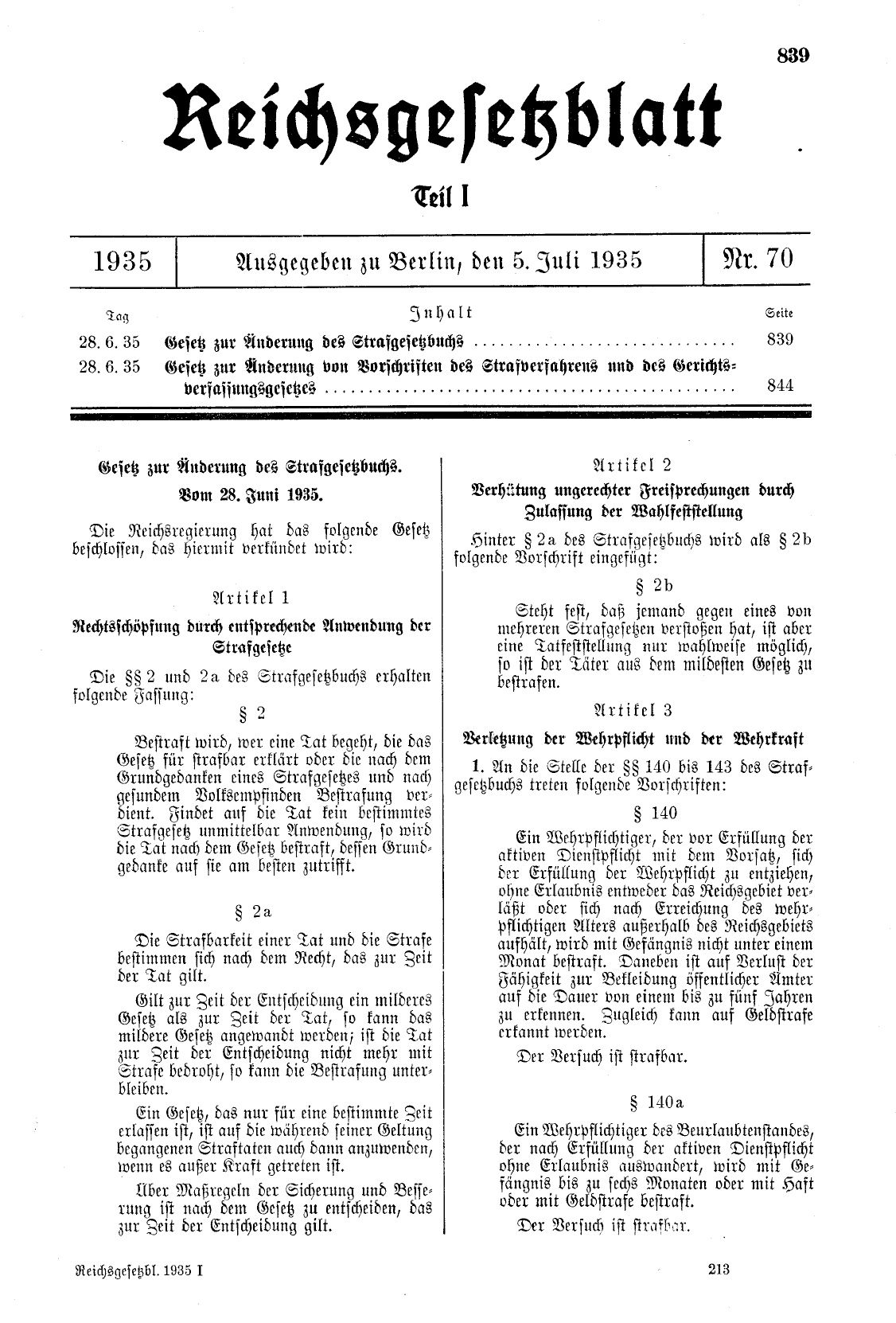

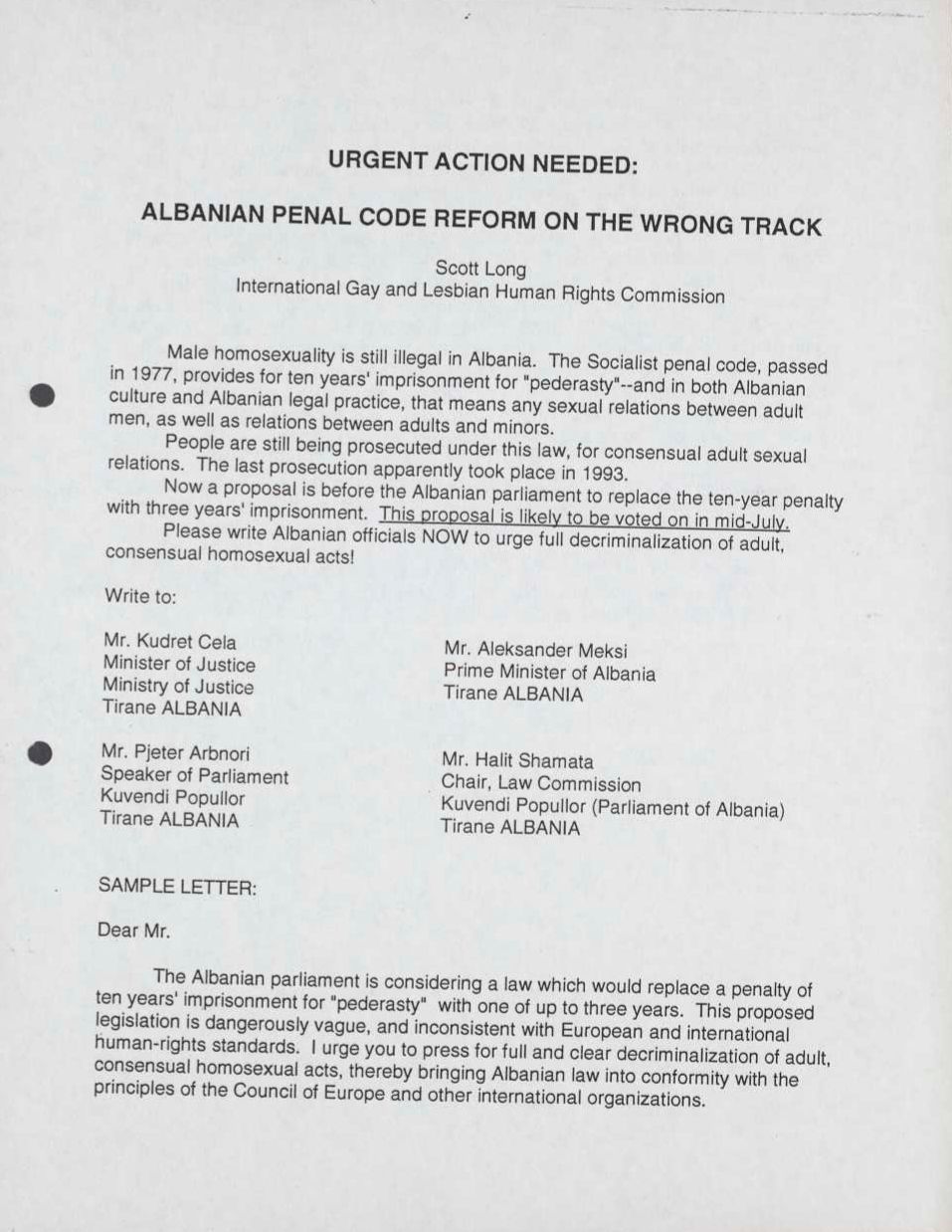

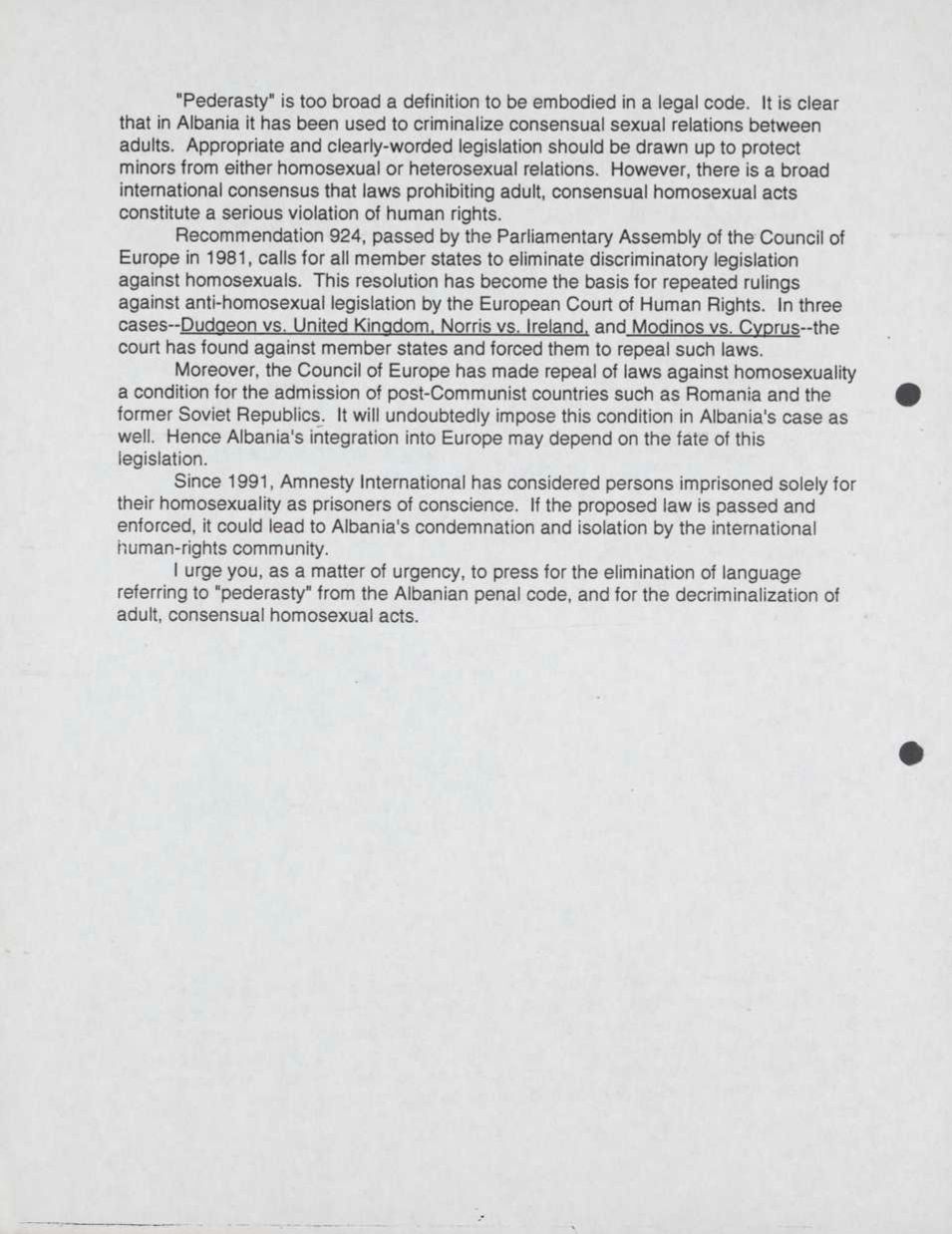

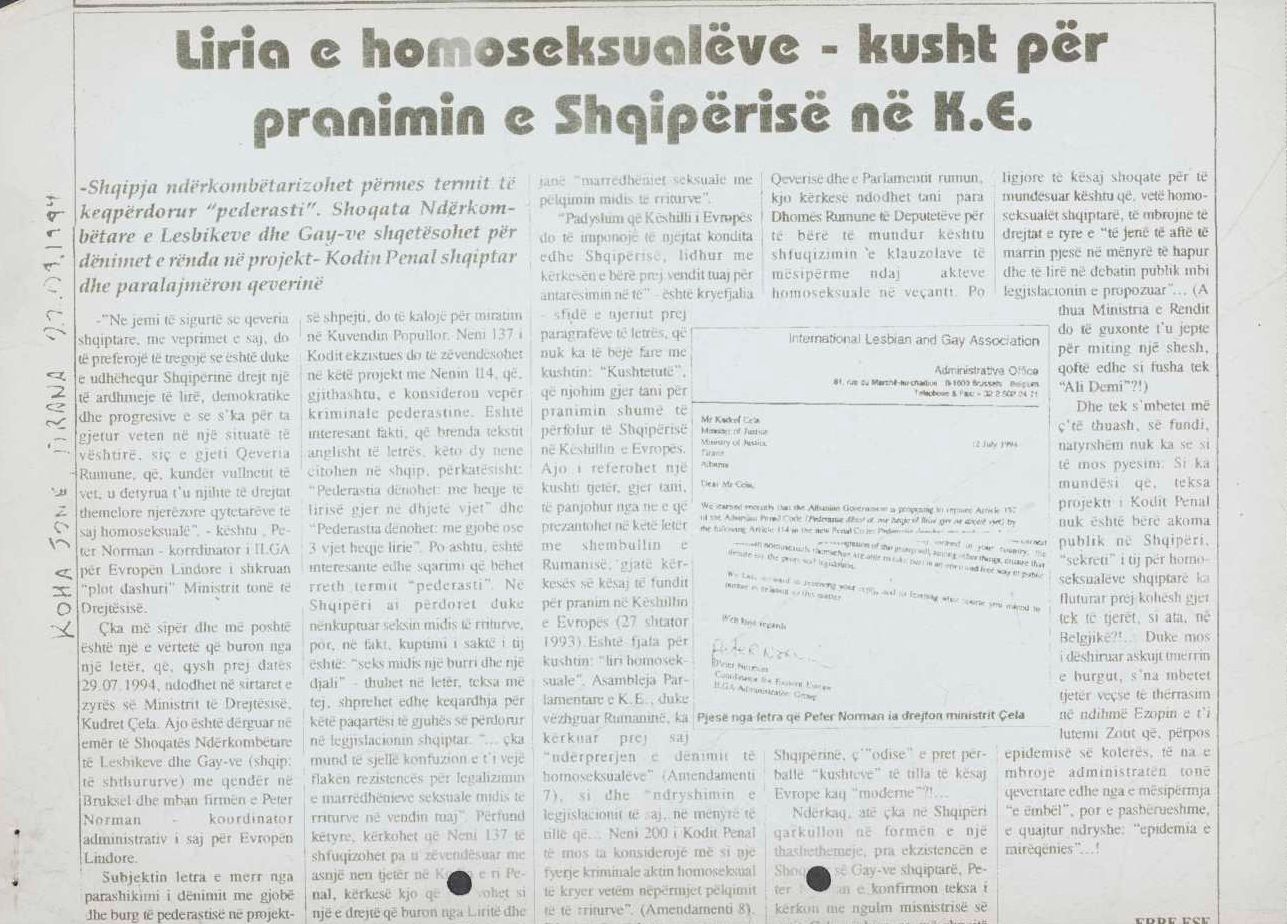

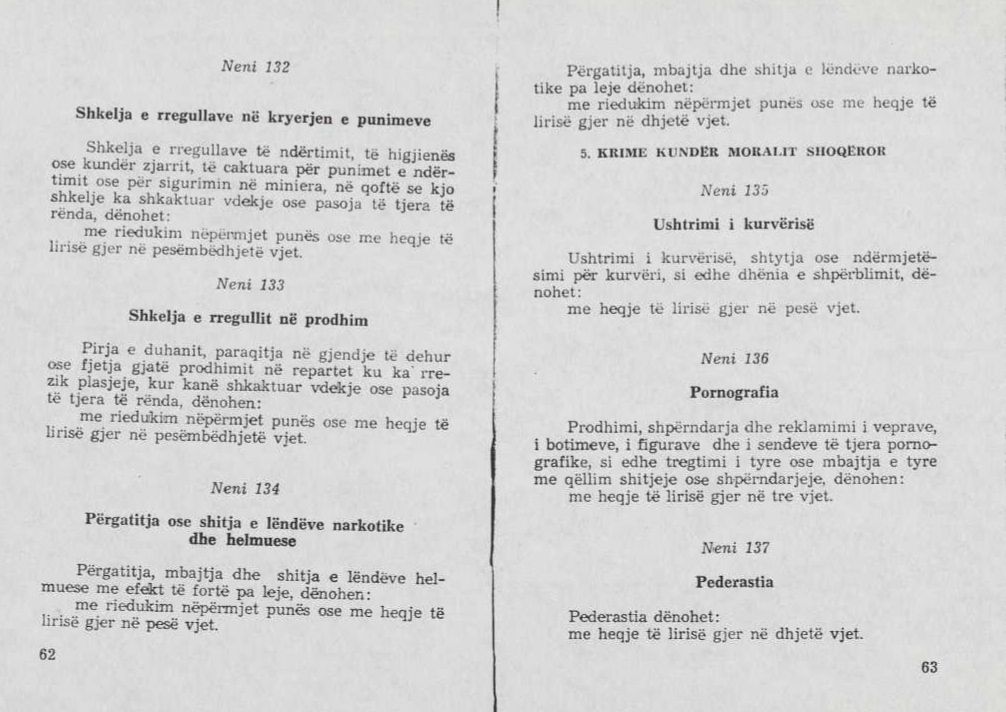

The aftermath of the Second World War brought to life new political constellations in Central and Southeastern Europe, in which, however, very little changed with regard to the legal treatment of homosexual acts. With the exception of Poland, which decriminalized homosexual acts in 1932, same-sex sexual activities were subject to general prohibition and punished with prison sentences throughout all countries initially belonging to the European Eastern Bloc, including SFR Yugoslavia. The most extreme articulation of these principles can be found in the Albanian Penal Code of 1977, where homosexual acts were punished with up to 10 years’ imprisonment.

Excerpt from the Albanian Penal Code of 1977

exhibition print

Blinken OSA

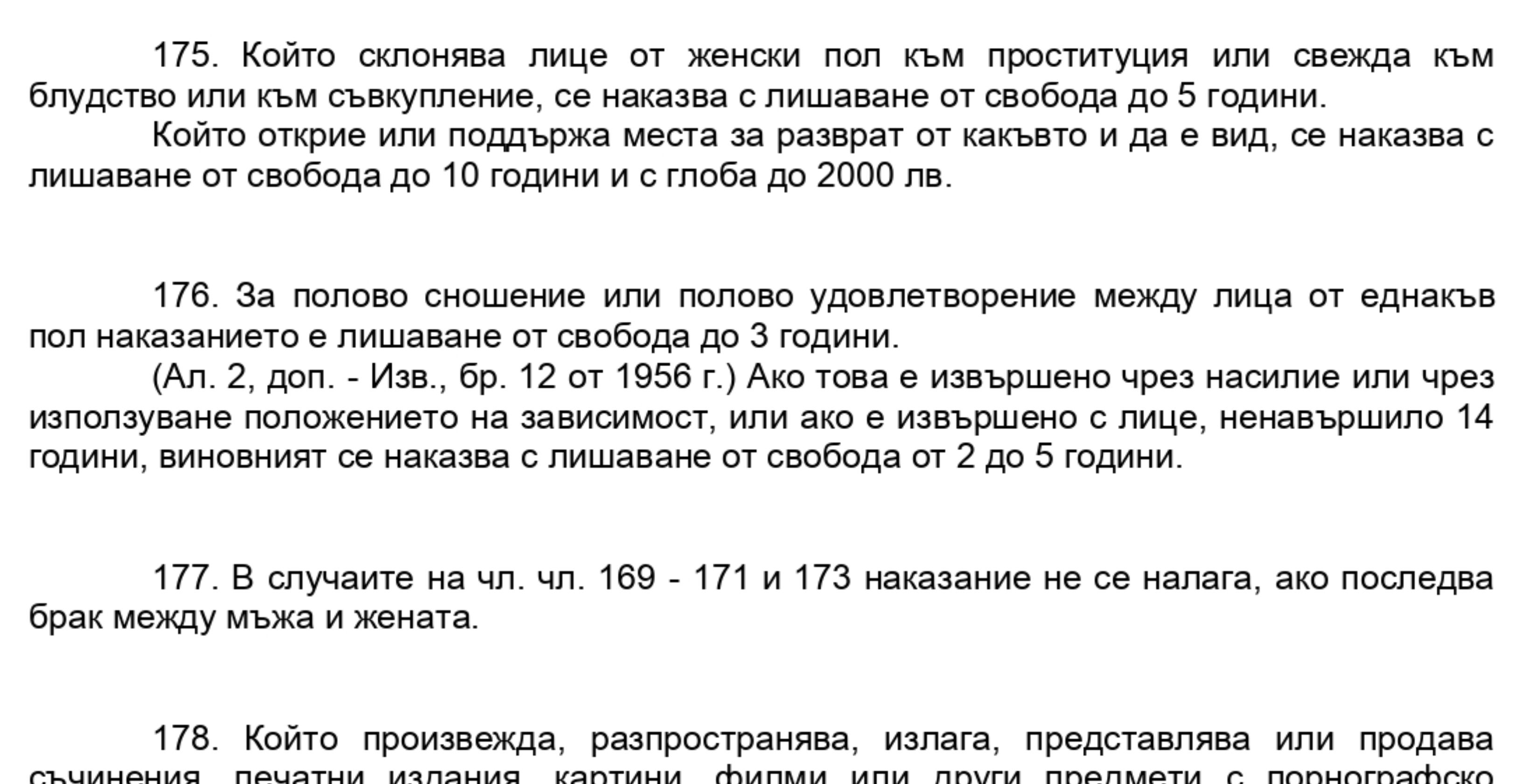

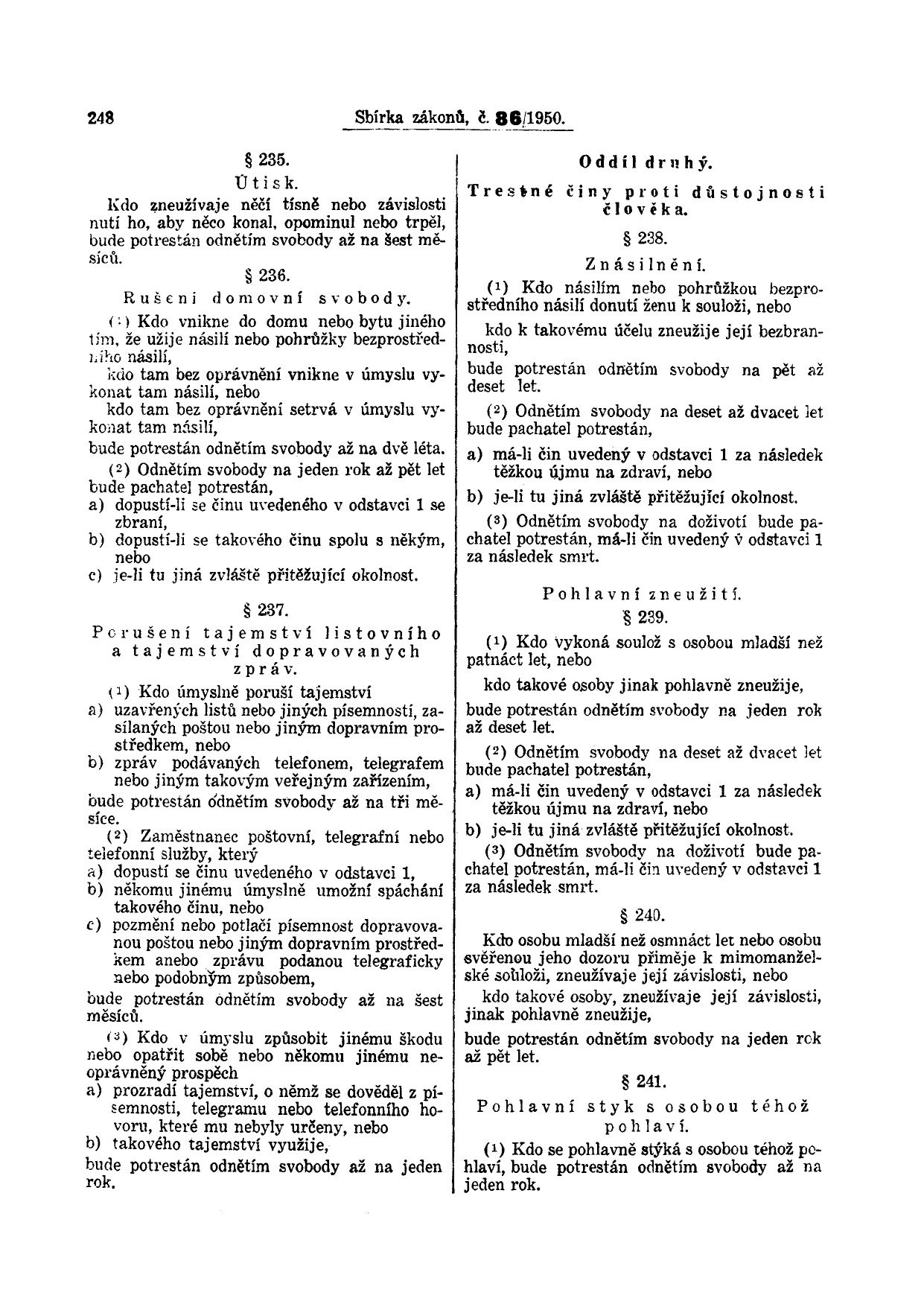

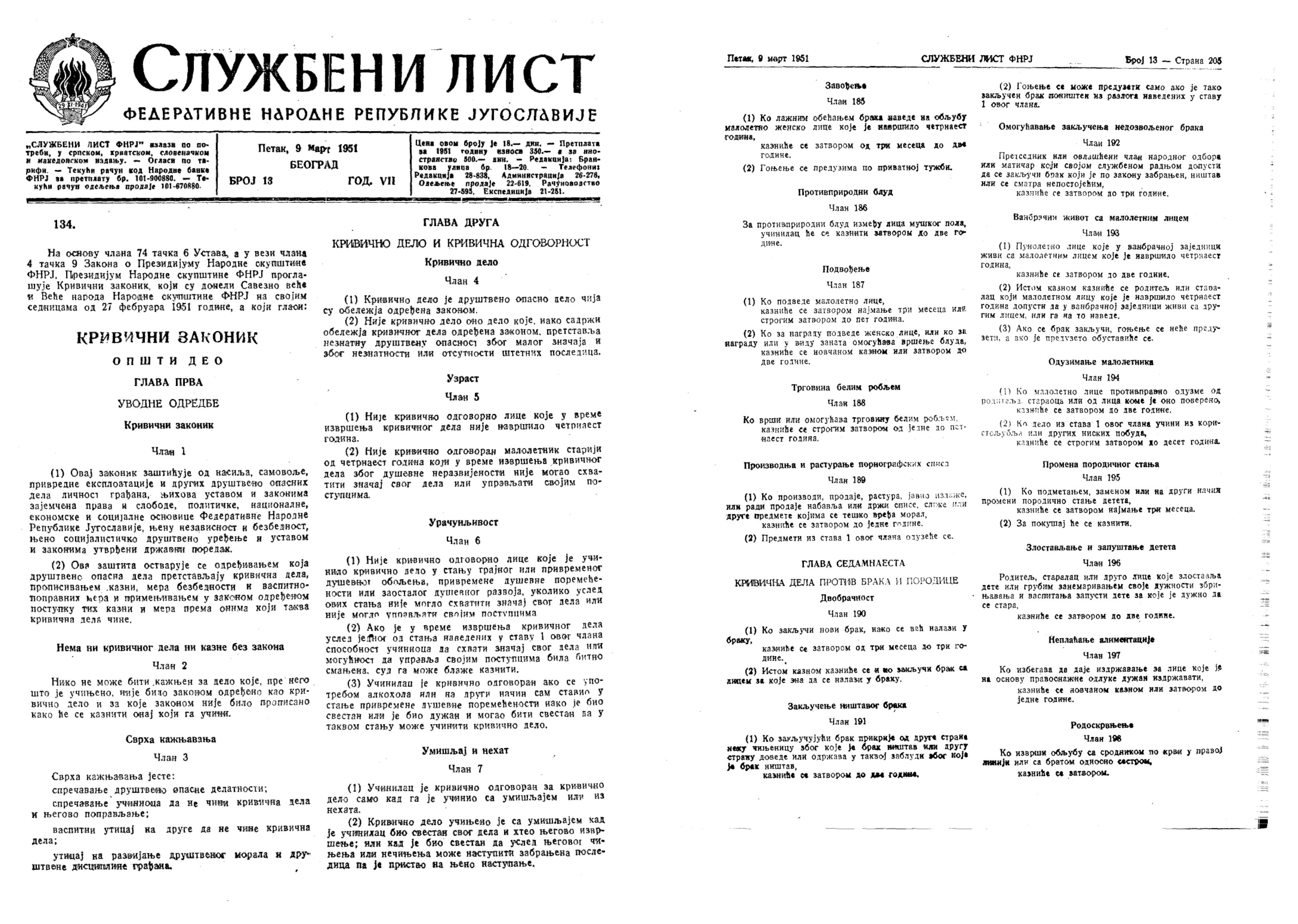

Excerpt of the Criminal Code of SFR Yugoslavia from 1951

exhibition print

Blinken OSA

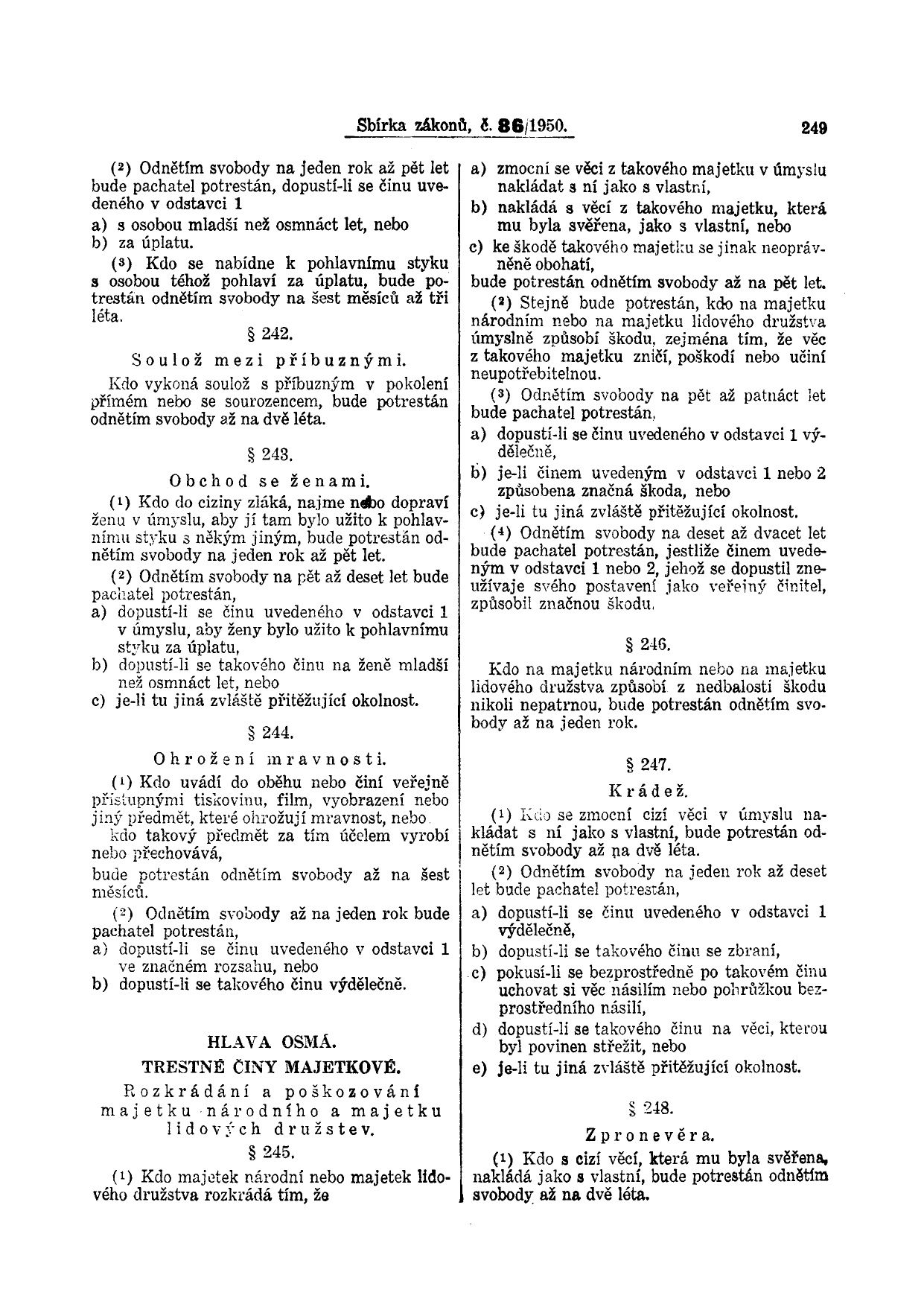

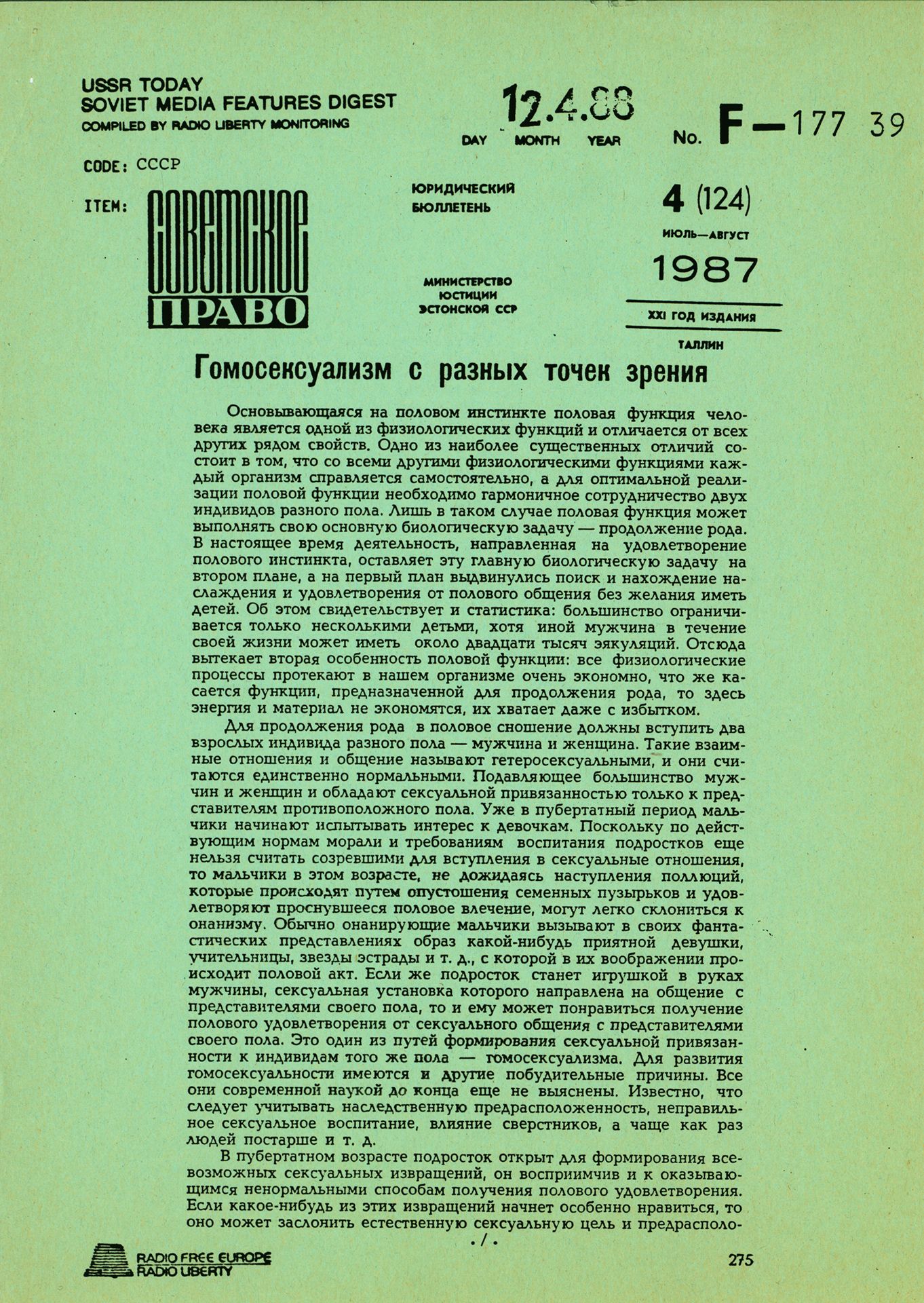

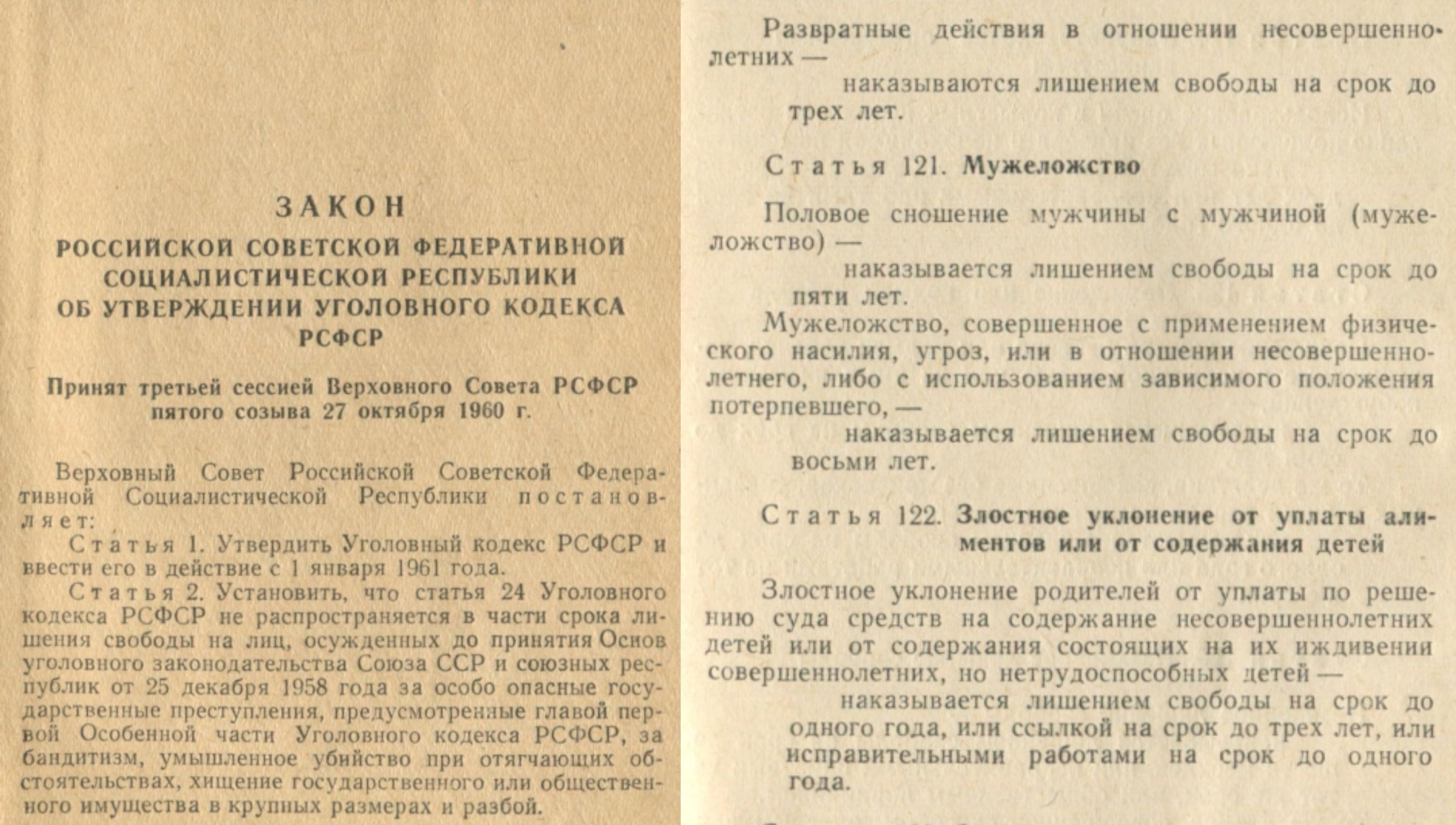

Excerpt from the Penal Code of the USSR from 1960

exhibition print

Blinken OSA

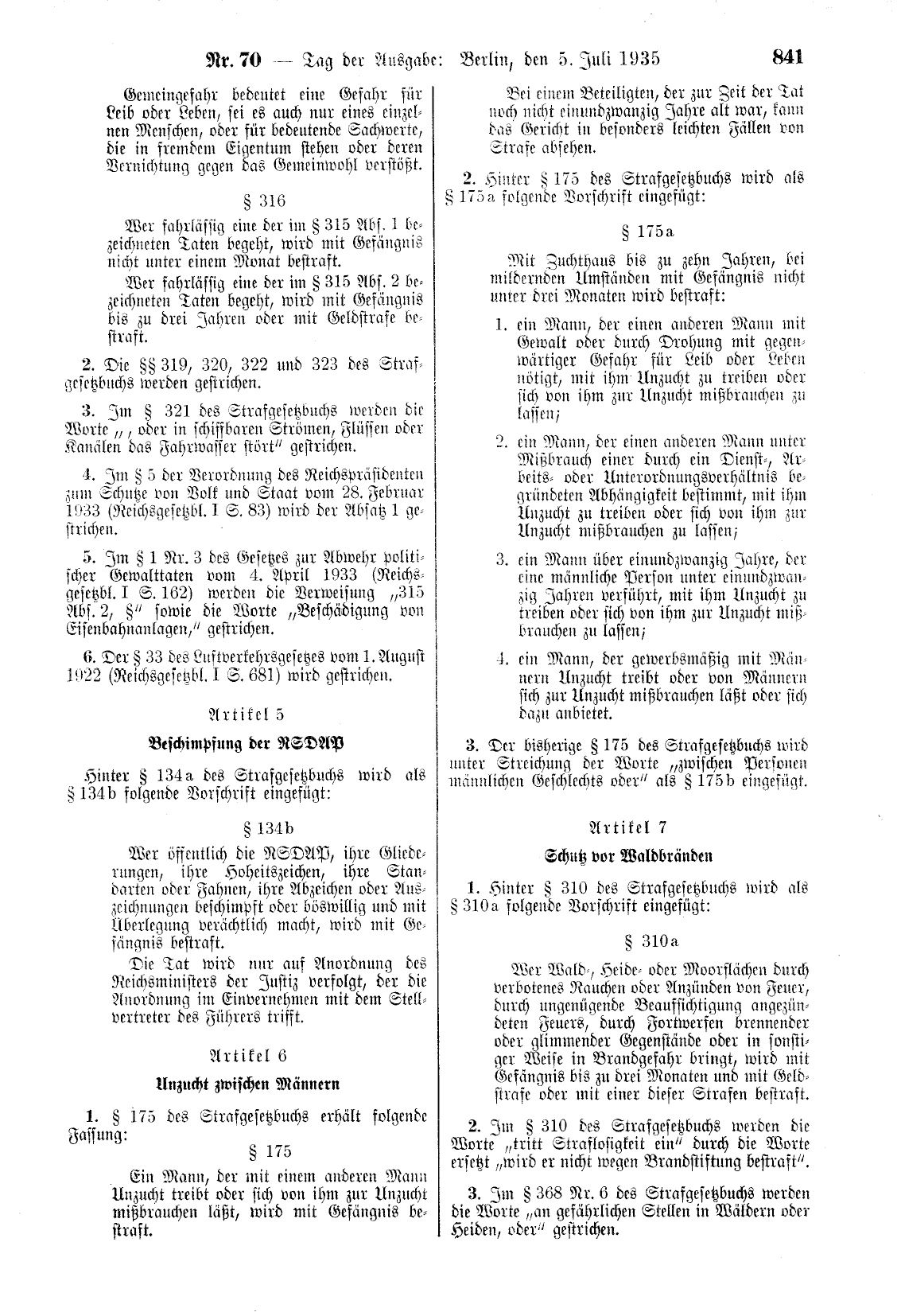

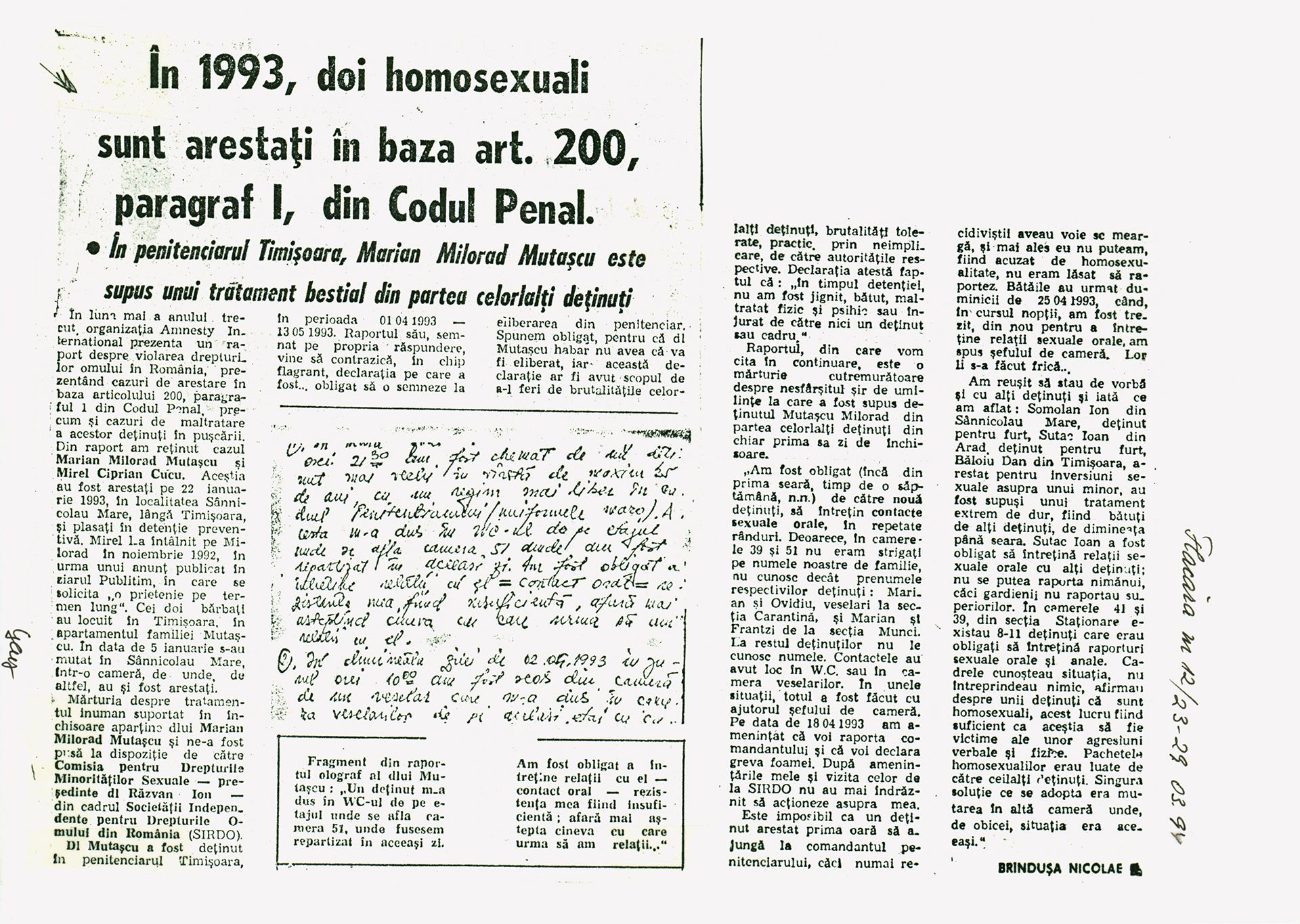

Art.200

Relațiile sexuale între persoane de același sex

Relațiile sexuale între persoane de același sex se pedepsesc cu închisoare de la unu la 5 ani.

Fapta prevăzută în alin. 1, săvîrșită asupra unui minor, asupra unei persoane în imposibilitate de a se apăra, ori de a-și exprima voința, sau prin constrîngere, se pedepsește cu închisoare de 2 la 7 ani.

Dacă fapta prevăzută în alin. 2 are ca urmare vătămarea gravă a integrității corporale sau a sănătății, pedeapsa este închisoarea de la 3 la 10 ani, iar dacă are ca urmare moartea sau sinuciderea victimei, pedeapsa este închisoarea de la 7 la 15 ani.

Îndemnarea sau ademenirea unei persoane în vederea practicării faptei prevăzute în alin. 1 se pedepsește cu închisoare de la unu la 5 ani.

The reasons for the (re-)criminalization of homosexual acts after the Second World War can hardly be generalized across all these countries. Beside their common efforts in establishing a legal order that can appropriately support the political orientation towards building a “communist society”, there were several other factors, whose balance, influenced the slight, but important, differences in the reasons for the criminalization and the severity of the punishments prescribed. These included the official and the scientific views on sex and sexuality in each of the countries, public disapproval and the lack of alternative forms of sexual behavior and relations, the necessity of stricter reproductive policies immediately after the Second World War, and the need to mirror the policies of the Soviet Union as paradigmatic for any communist country. Whichever of these factors was predominant as a reason for criminalization, it was coupled with a more basic postulate about homosexuality which lay behind the principles of the Marxist-Leninist criminology of the late 1940s: namely, homosexual acts ensue from acquired sexual corruption of the will. They are motivated by the desire of a person for a bourgeois way of life and as such they should be considered antagonistic to socialist morality; in many cases homosexual acts were also characterized as counter-revolutionary provocations and offences.

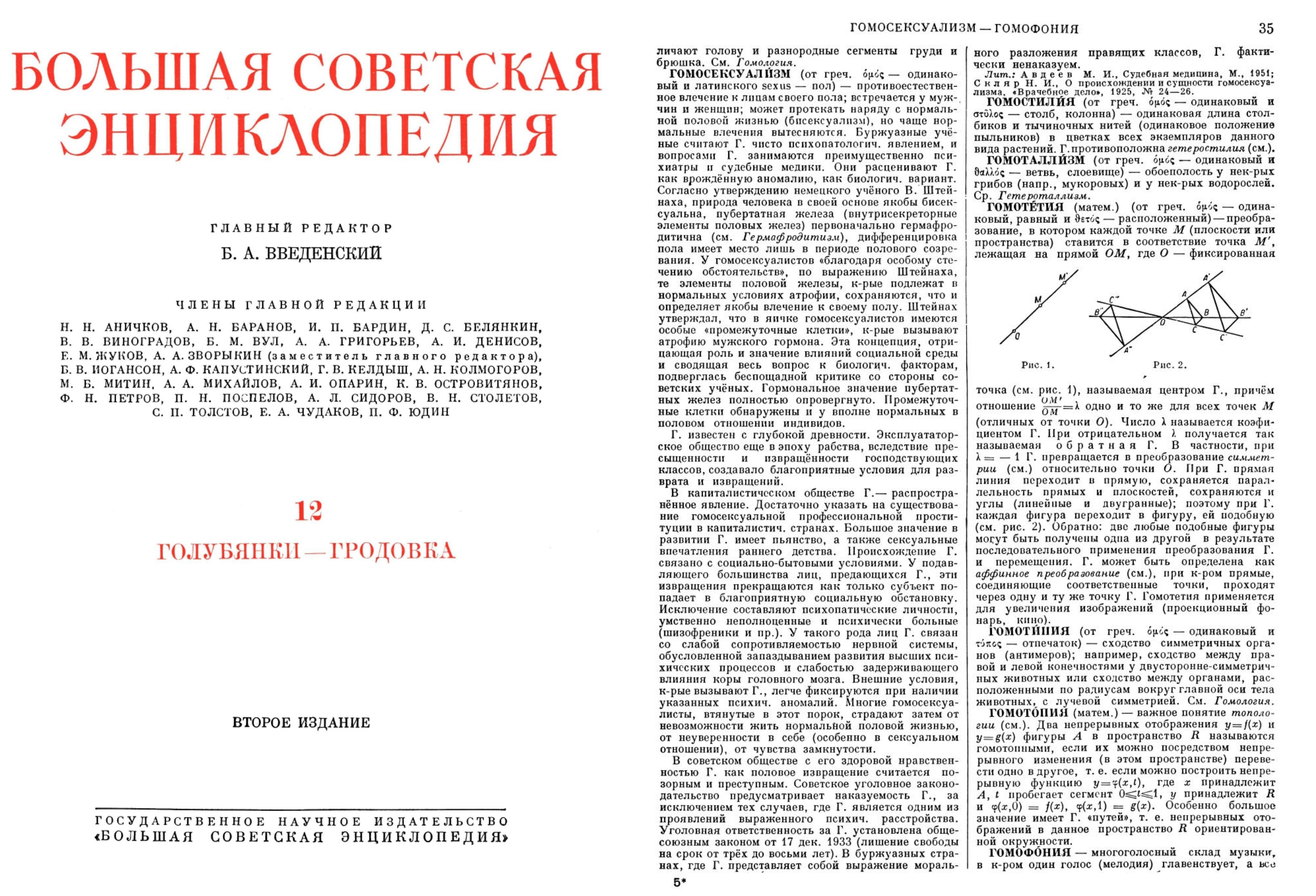

Excerpt on homosexuality from the “Great Soviet Encyclopedia”, 1952

book excerpt, exhibition print

Blinken OSA (Excerpt originally used in the OSA “Sex and Communism” exhibition)

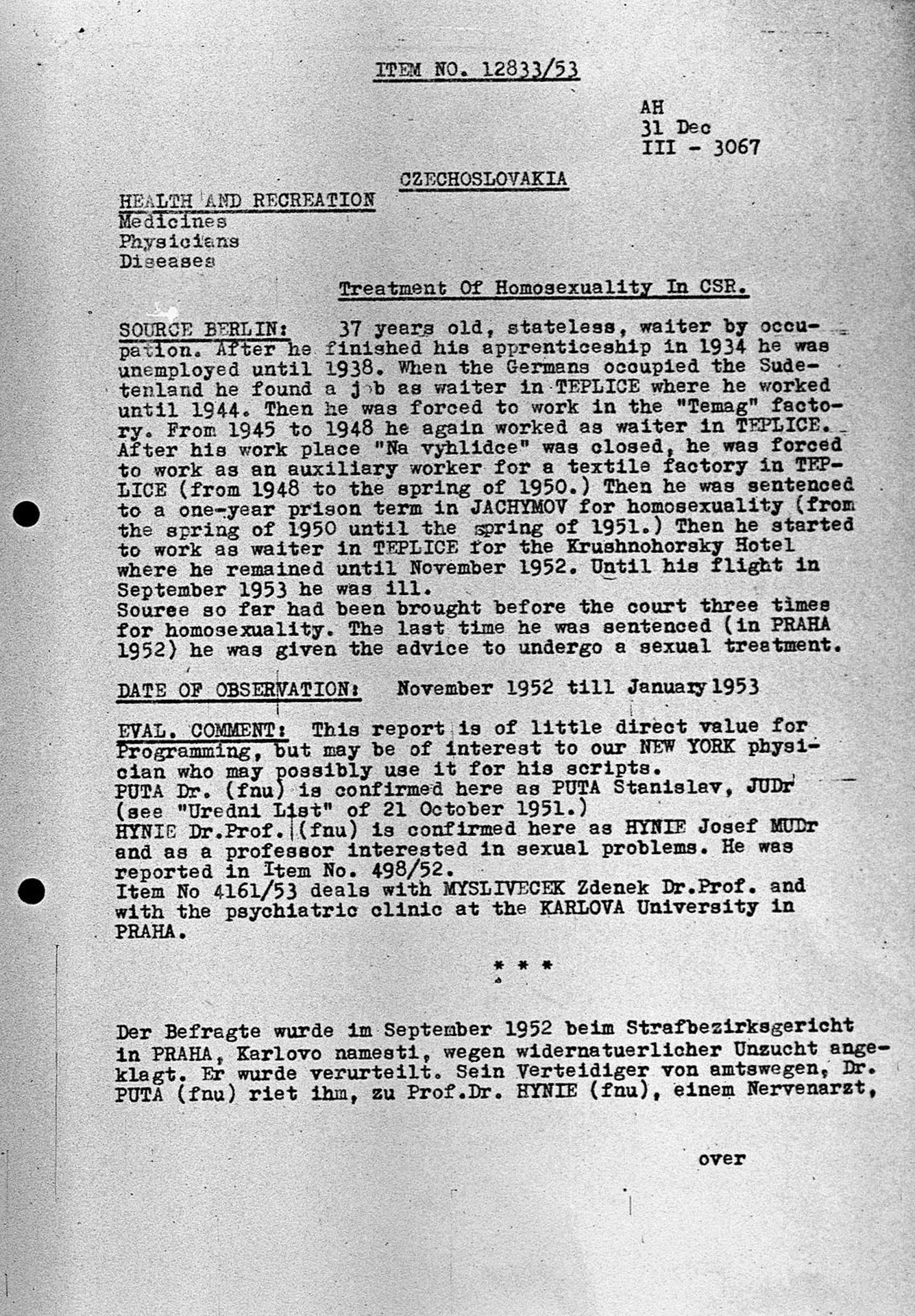

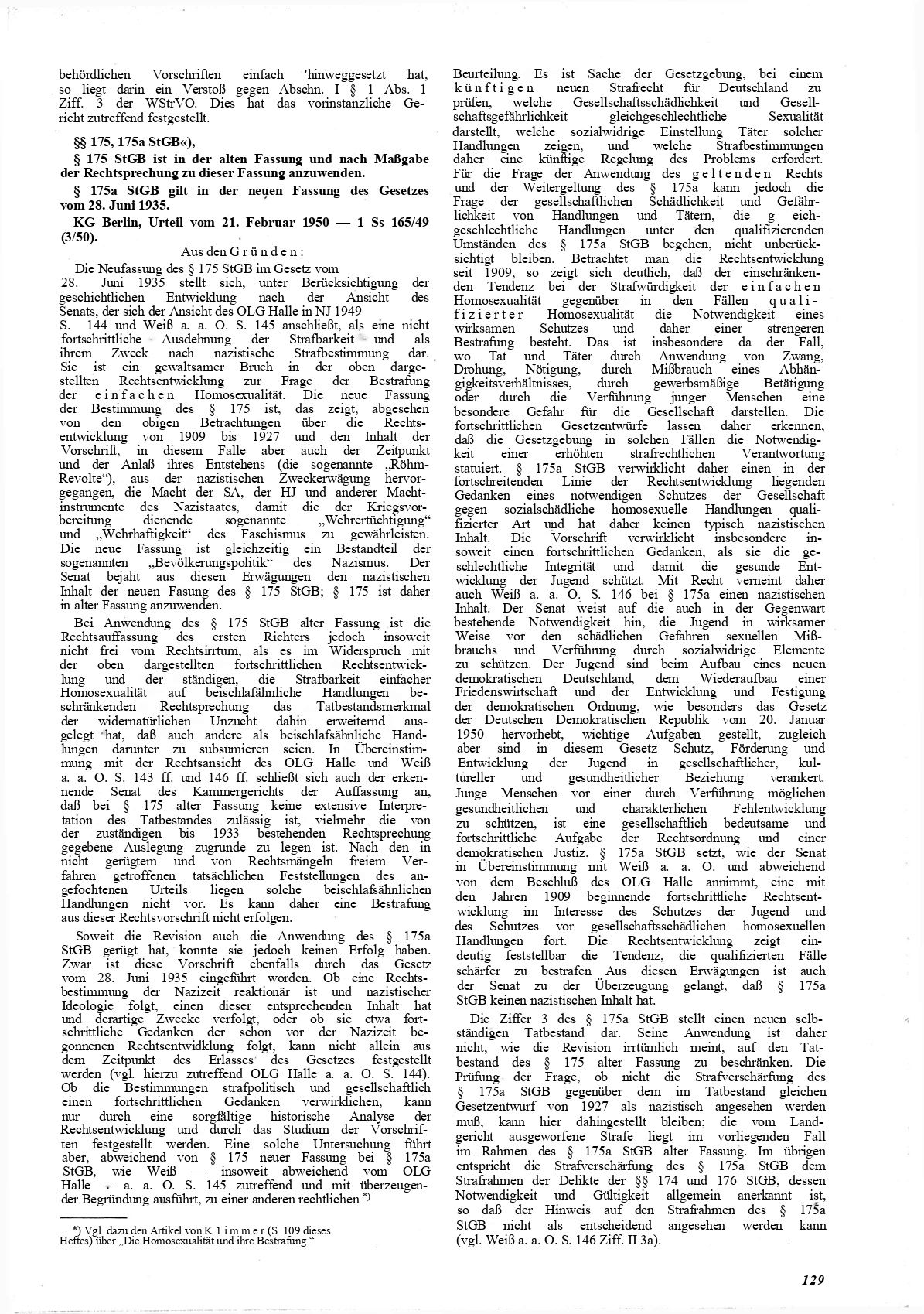

Justification of the Supreme Court in Berlin for the introduction of a general criminalization of homosexual acts in the DDR, 1950

article appearing in “Neue Justiz” 4, exhibition print

Blinken OSA

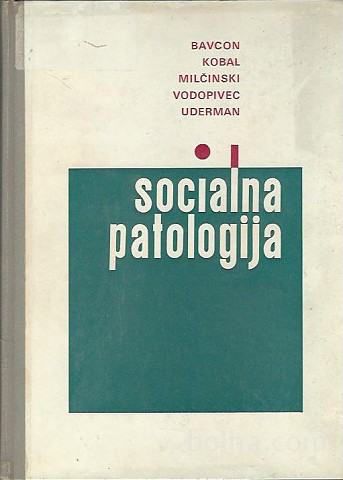

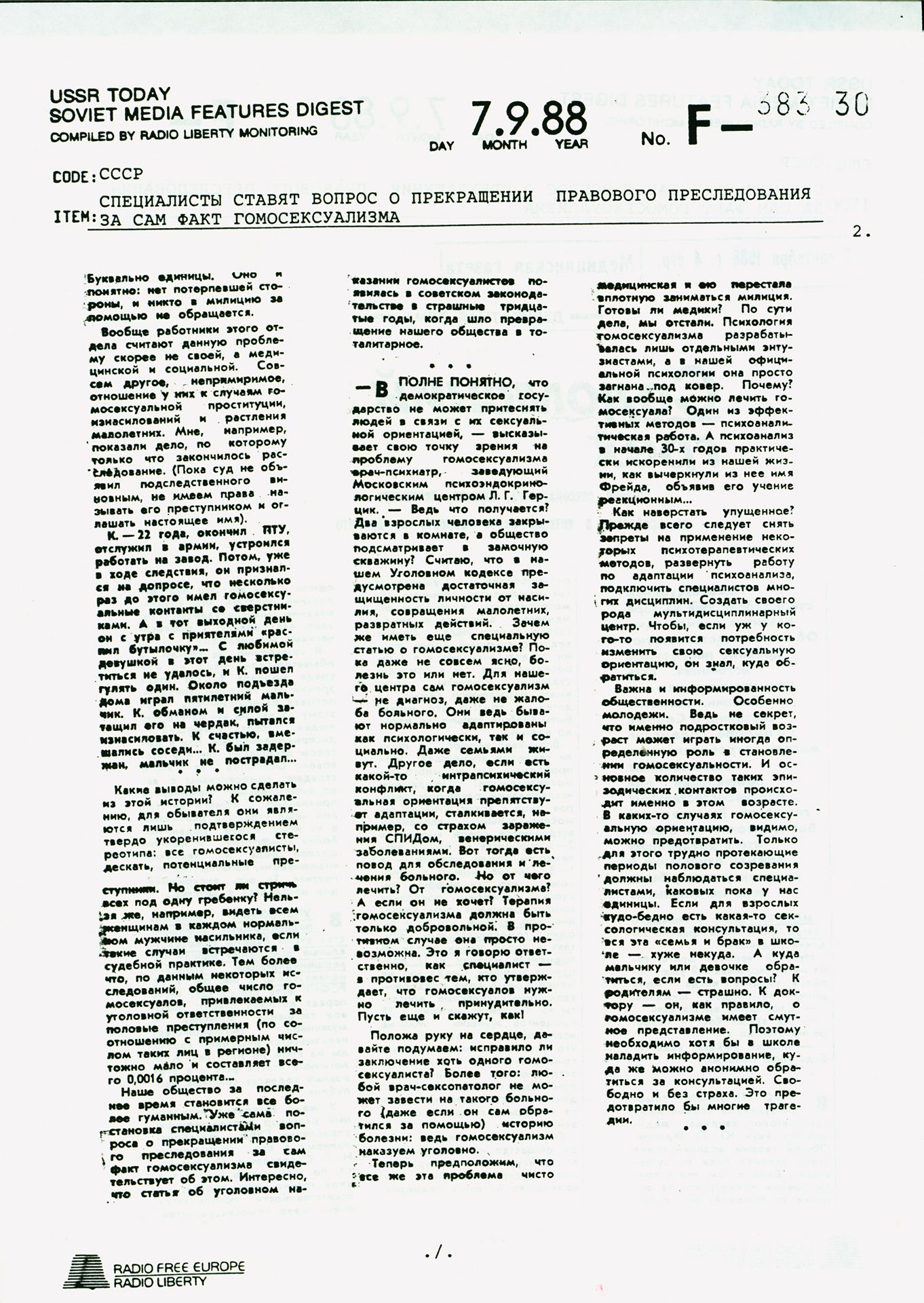

After the 1960s, insights from psychiatric research conducted since the 1950s as well as from sexology and social pathology contributed to a scientific change in the attitude towards homosexuals, most notably in Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and Hungary. This alteration was manifested in the understanding of homosexuality within the legal sphere as well. As claims about the genetic pre-determinacy of homosexuality gained prominence in psychiatric and sexological research, homosexuals started to be seen not as persons with corrupted desires but rather as “natural perverts” who cannot be held responsible for their sexual inclinations. In some cases, such as in SFR Yugoslavia, it was not sexological, but rather social pathological insights that proved to be crucial for a reform of the system of sexual offenses as they recognized the failures of punishment to deter offenders from committing homosexual acts in future.

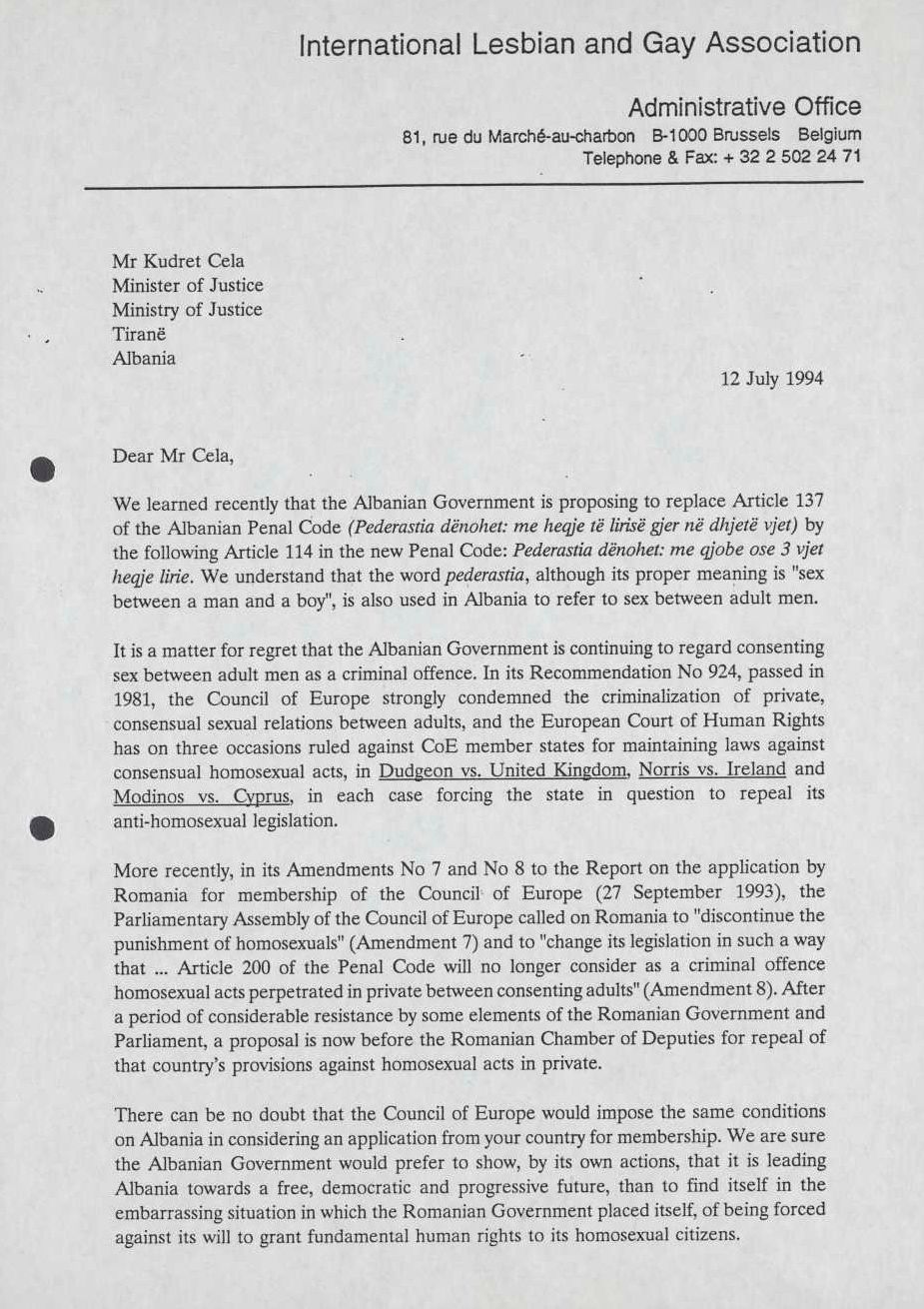

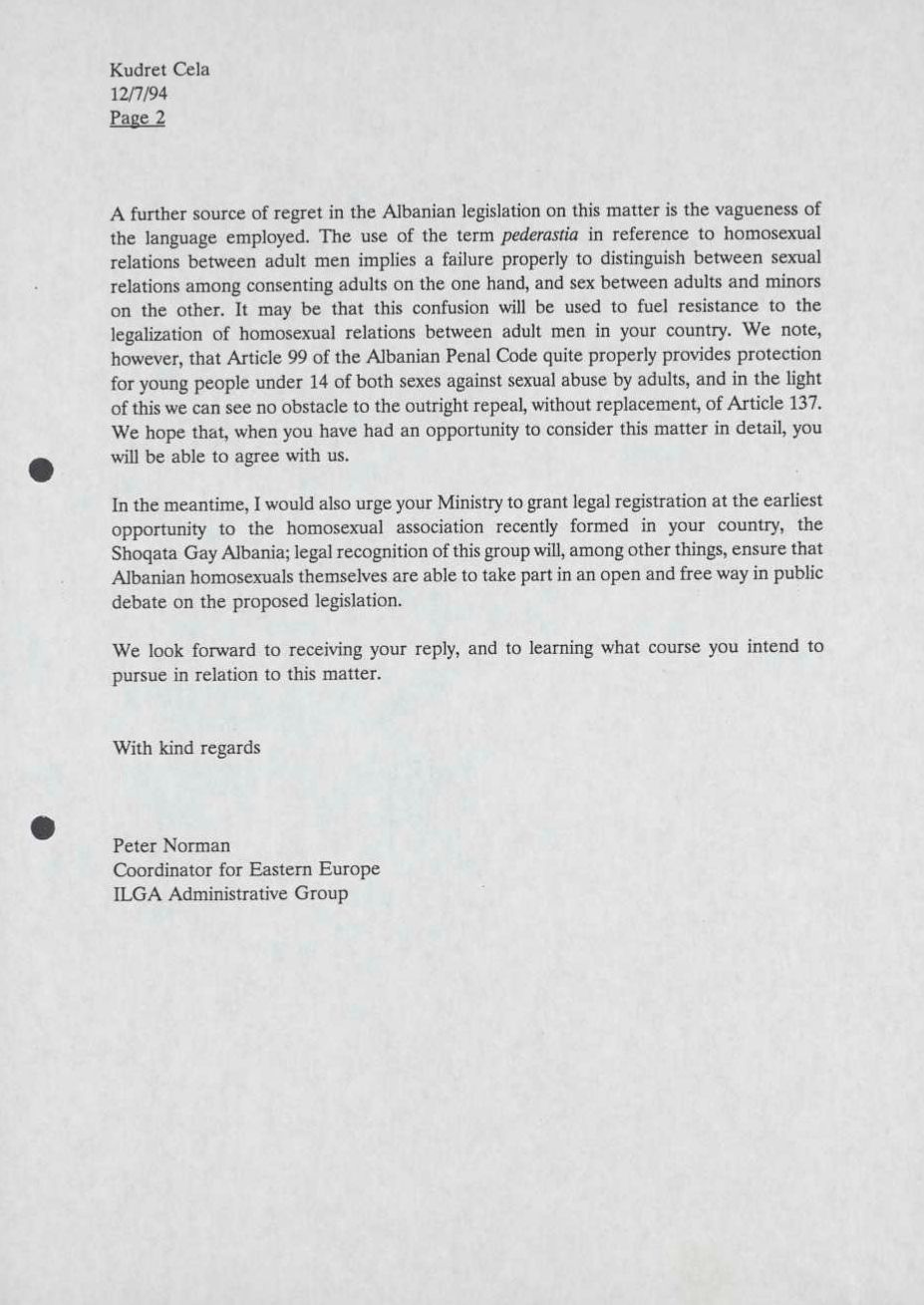

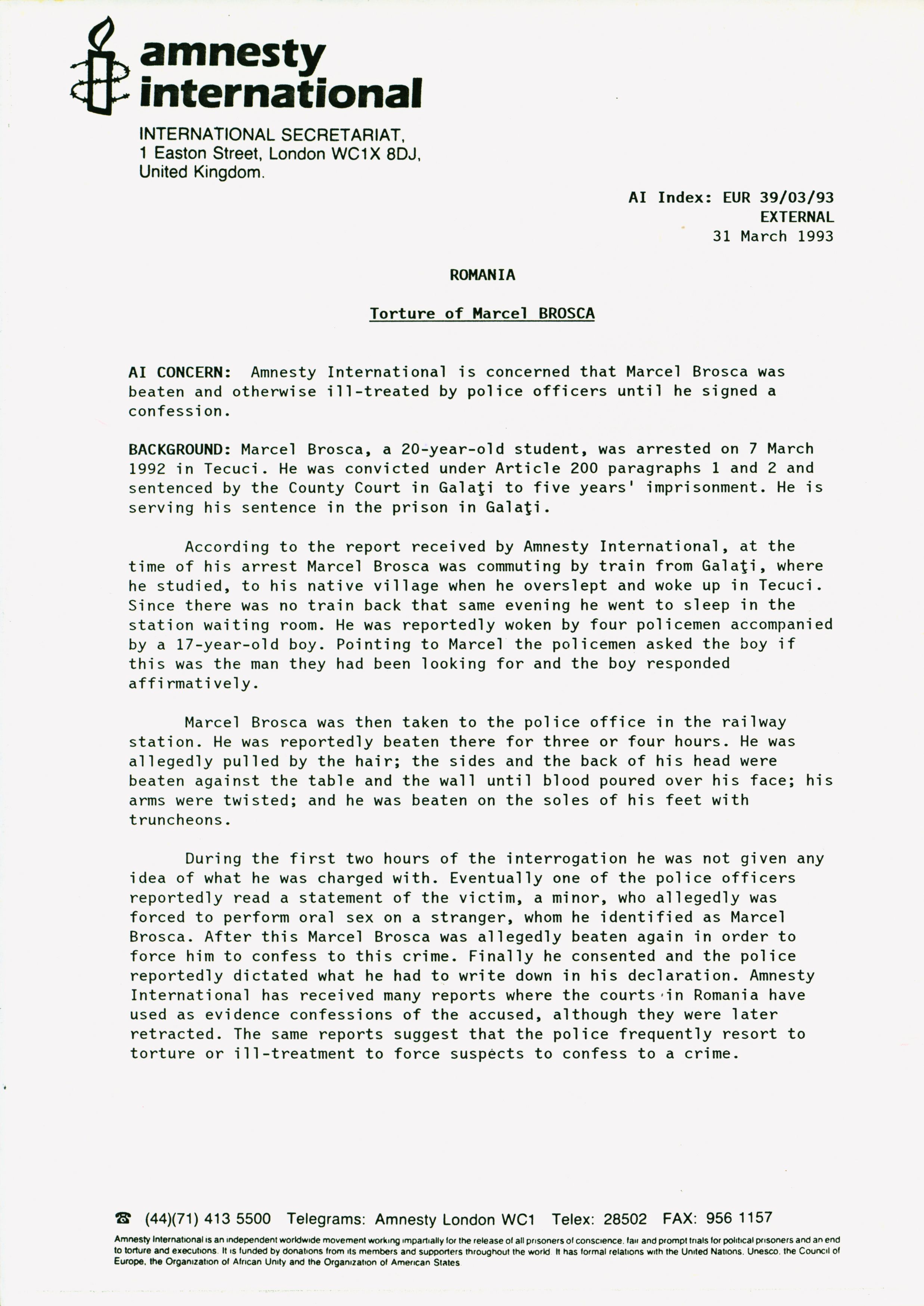

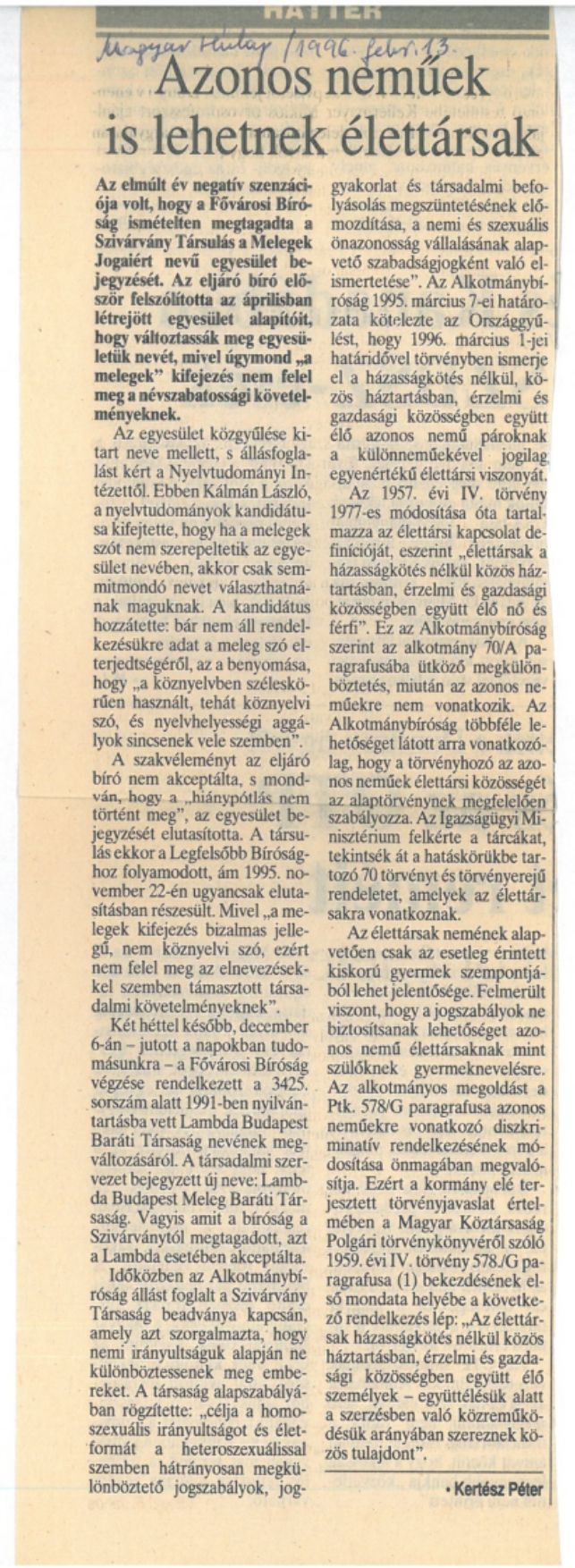

The findings of these scientific studies contributed considerably to the processes of decriminalization and in some cases proved to be even detrimental. However, as in the case of criminalization, there were also additional reasons that were used as justifications for the decriminalization which were specific to the political and socio-cultural context of each country. Two general trends are, however, worth mentioning. While in the countries which decriminalized homosexual acts in the 1960s and the 1970s, the laws were passed without the involvement of the homosexual community and as a matter of individual initiatives and appeals by medical and legal experts, in the countries which decriminalized homosexual acts in the 1990s the process was subject to organized domestic and international pressure by registered gay and lesbian organizations, their respective communities, international lobby groups and LGBT+ organizations, human rights organizations, and allies in powerful intergovernmental and supranational bodies.

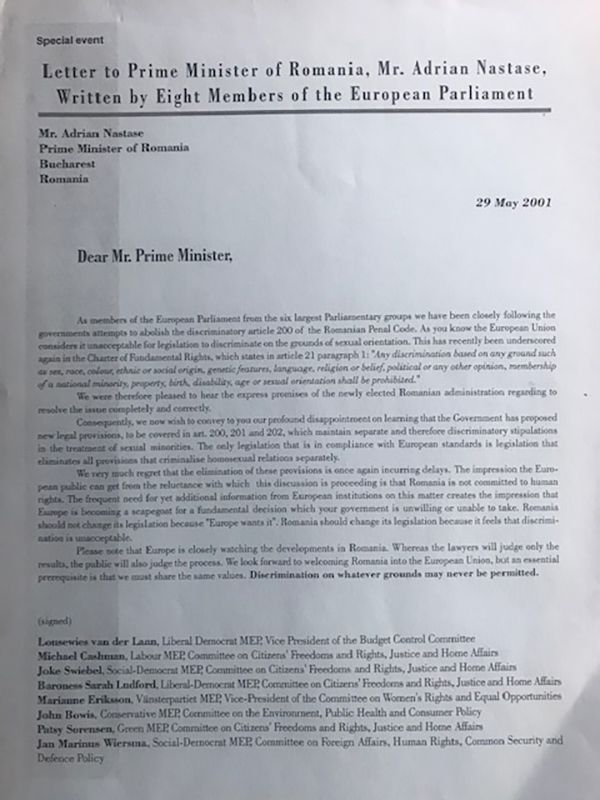

Members of the European Parliament ask the Romanian Prime Minister, Adrian Năstase, to repeal Article 200, 2001

correspondence, exhibition print

ACCEPT, Bucharest

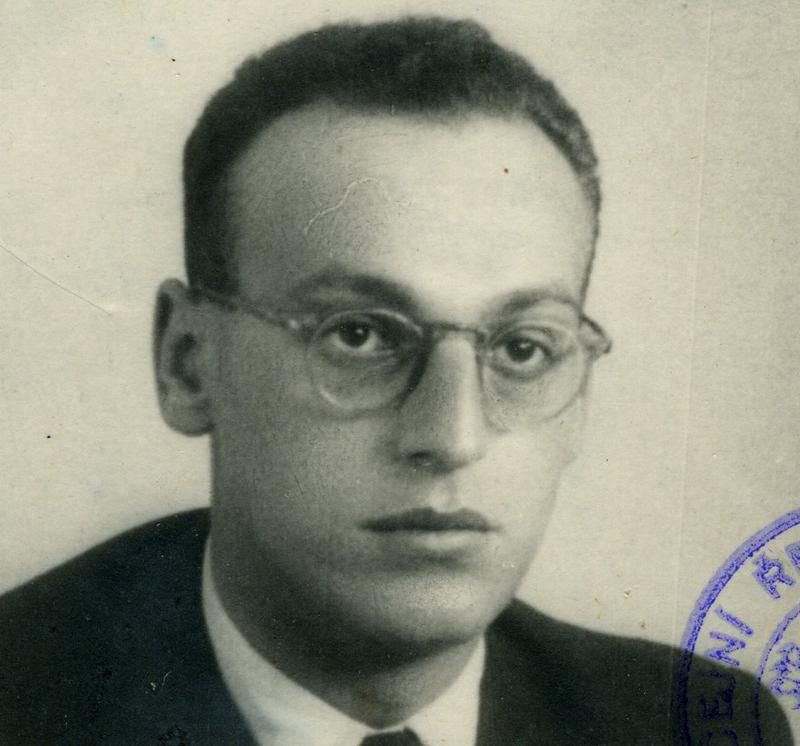

The consequences of the criminalization of homosexual acts for the everyday lives of gays and lesbians should not be reduced only to the threat of prison sentences. The prison sentences were accompanied by an “orchestra” of repressive instruments and actions which the state used to control and punish their behavior. As many of the documents displayed in the section below reveal, homosexuals were expected to conceal their sexual inclinations, and keep silent about them; intrusion into their privacy was frequent; they were easy targets for blackmailing, common object of public shaming and widely discriminated against on the base of their sexual orientation. An important and commonly asked question in regard of the decriminalization is thus, whether and how it changed this social situation of theirs? Although the decriminalization excluded the threat of draconian prison sentences of homosexuals, to a large extent the everyday lives of gays and lesbians, especially in the countries who passed this process in the 1960s and the 1970s, seems to remained unchanged with the same accompanying threats mentioned above being still tangible, although to a lesser degree.

Interview with Atanas Svilenov, a person tried in 1964 for homosexual acts in Bulgaria, several years before the decriminalization, 1997

video excerpt from the documentary “An Ambiguous Feeling”

Blinken OSA

Excerpt from an interview with Mariana Cetiner, the last prisoner sentenced under Article 200 in Romania, 1998

video

Amnesty International and ACCEPT, Bucharest

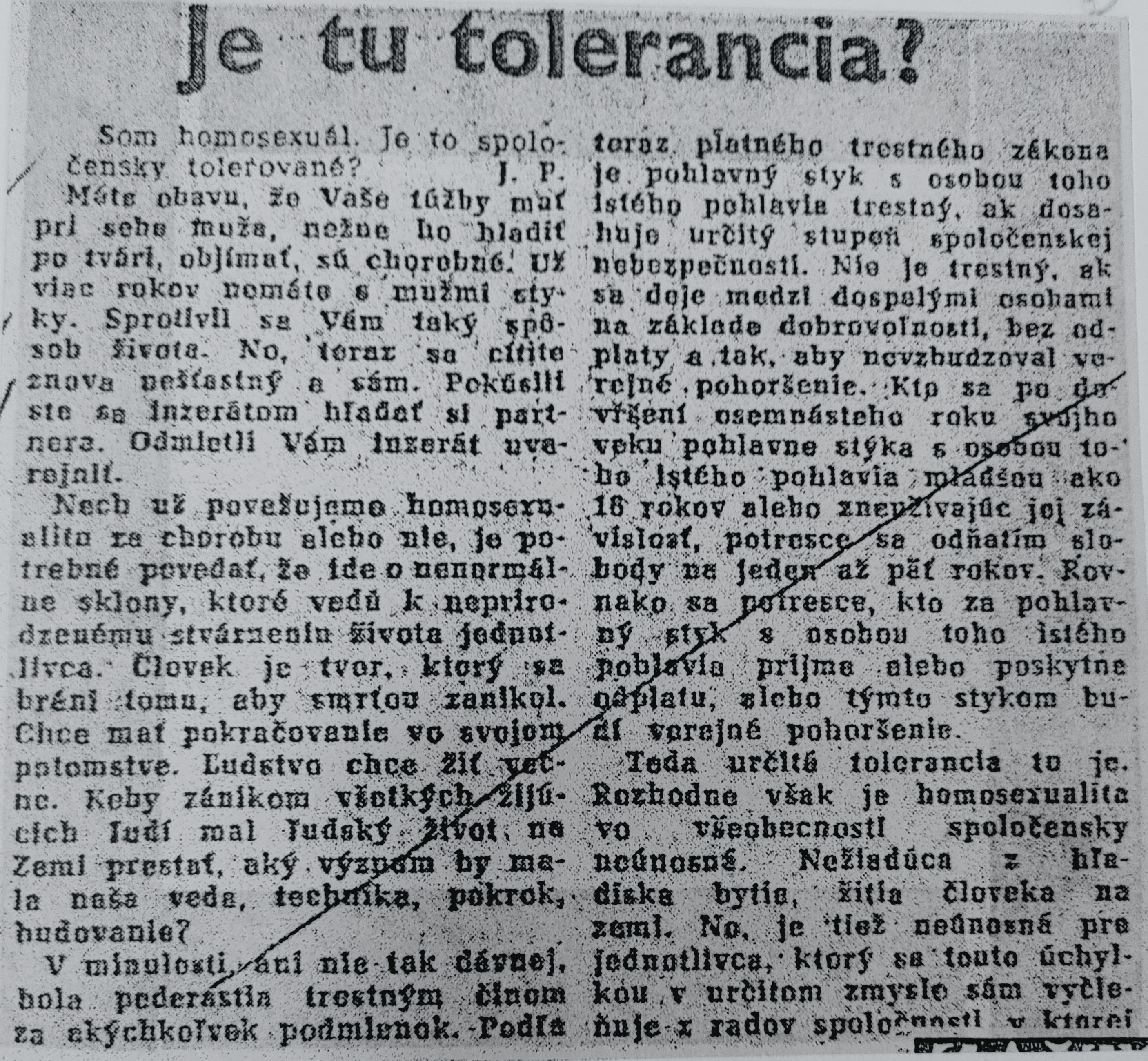

Newspaper advices: “I am homosexual: does society tolerates this?”, 1972

article in the Czech “Práca”, exhibition print

Blinken OSA (Excerpt originally used in the OSA “Sex and Communism” exhibition)

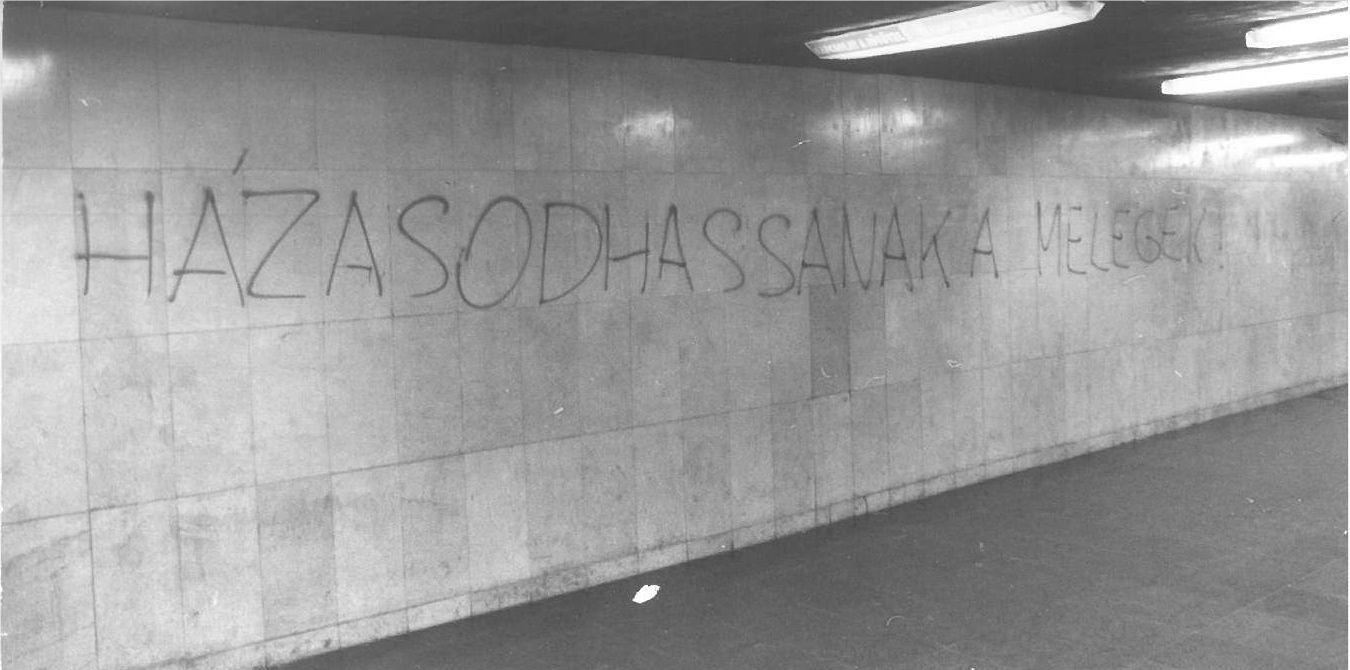

The decriminalization of same-sex activities should be seen as just a small step in the struggle for the legal recognition of homosexuals and their gender identities. It is mainly after the 2000s that, in most countries in Eastern, Central and Southeastern Europe, the prohibition of discrimination based on sexual orientation would emerge and laws against hate crimes based on sexual orientation would be enforced. Marriage and partnership rights for same-sex couples, together with rights to joint adoption, have still not been advanced in some of these countries’ legislatures. In others, such as Hungary’s, they have been legally curtailed, as the self-proclaimed “illiberal-democratic” regime of Viktor Orbán in 2020 blocked the opportunity for same-sex couples to form families and severely restricted their opportunities to adopt children as single parents, subjecting their appeals to exceptional and discretionary governmental approval.